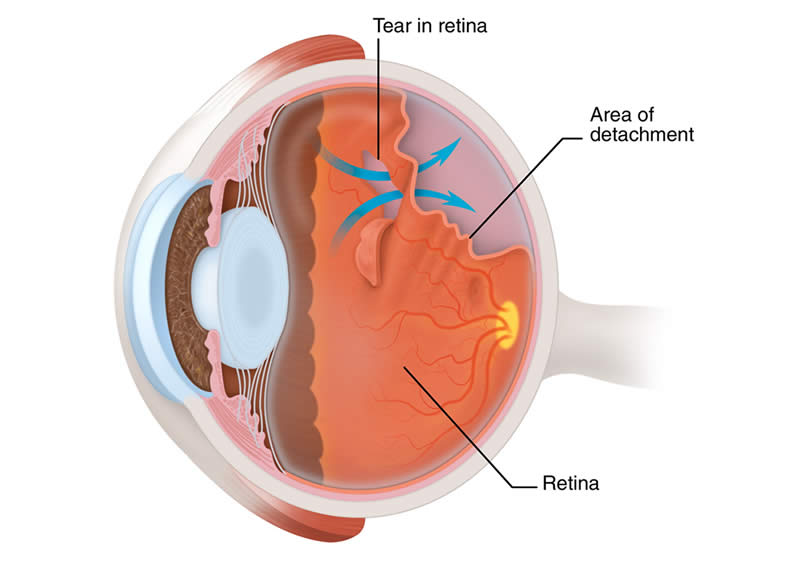

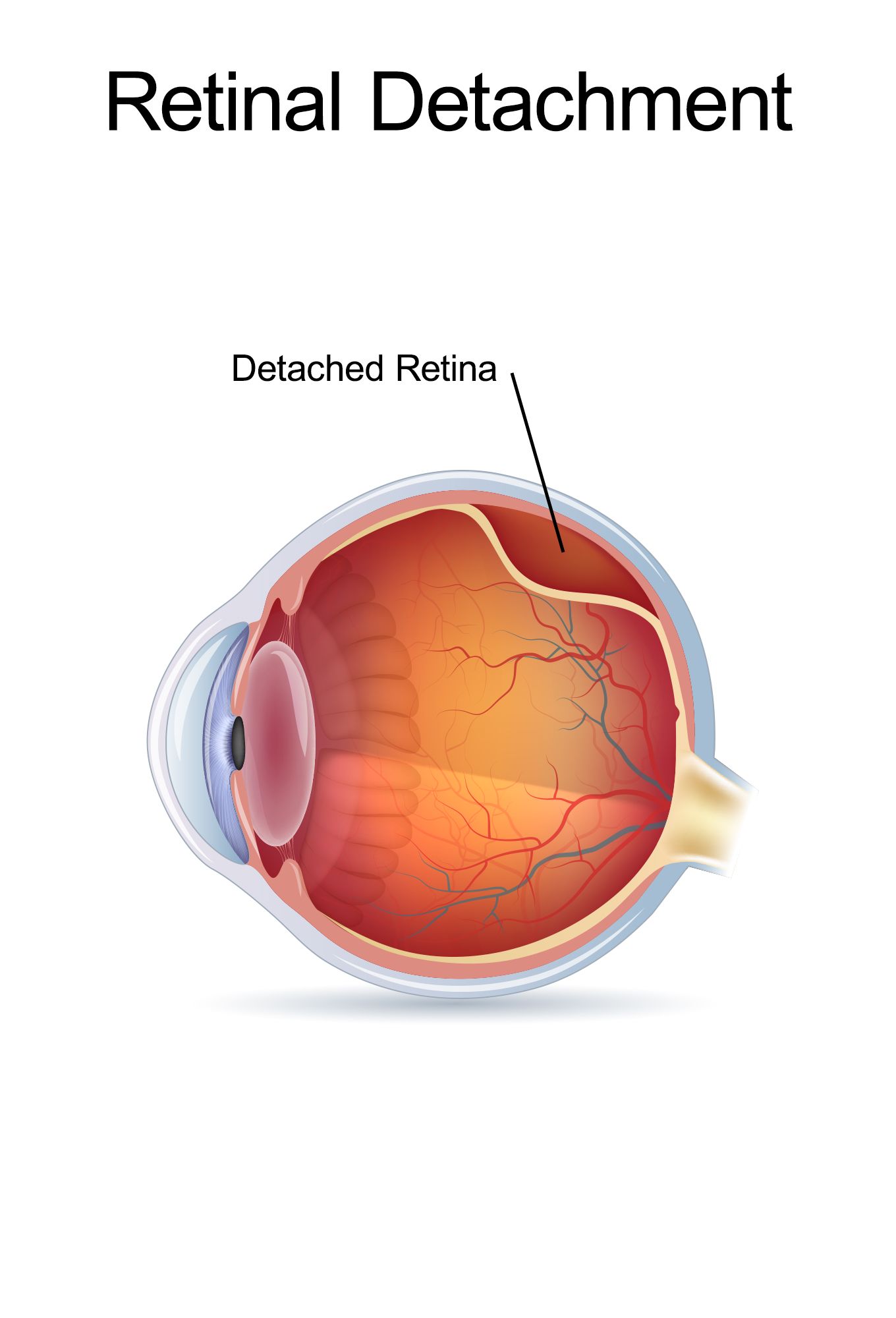

The vitreous tends to be more stuck to the retina around patches of lattice degeneration making an individual more vulnerable to developing retinal tear or retinal detachment during or following recent vitreous separation. This mechanism, or cause, of retinal detachment can be seen especially in younger patients before the vitreous gel separates.

Within these patches of thinning, multiple holes may develop spontaneously allowing fluid to accumulate leading to retinal detachment. Others are born with a tendency to develop peripheral patches of thinning called lattice degeneration. These conditions tend to be more common in near-sighted individuals, especially those with higher refractive errors (who need stronger spectacles or contact lenses). As the fluid builds up underneath the retina, retinal detachment, a blinding condition, can occur. If the retinal tear remains unrecognized and untreated, then fluid can rapidly accumulate through a defect (or multiple retinal defects). More rarely, the vitreous will remain attached to a part of the retina resulting in the development of one or more tears as the vitreous tries to pull away. Most of the time the vitreous will separate cleanly without complication, but the patient may notice flashes and/or floaters. As the eye ages, the vitreous will shrink and separate from the retina.

Retinal tear and retinal detachment are part of the same spectrum of disease requiring urgent, and frequently emergent, evaluation and treatment. In the young eye, the vitreous gel is in direct contact with the retina, the specialized, multilayered nerve tissue which lines the back of the eye.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)